Big George, George Jr., and Baby George

A tribute to the George Foreman Grill, boxing, and the Georges in my life

Daddy’s eyes are glued to the screen. He’s pulled a canvas-backed director’s chair across the wooden living room floor so he won’t miss a single punch. I scoot next to him. I like being near when he’s in a good mood. I watch him react to blows, analyze shots, and talk to the boxers. Mommy walks by us. Normally, she would scold me for sitting this close to the set. Maybe she doesn’t say anything because I’m now seated on Daddy’s lap. My back presses against his fat belly. By keeping my father company during fights, I learn the sport. I cheer alongside him if his favored competitor wins. I don’t cringe when I see boxers bleed from jabs or cuts. Daddy explains that these hurts come with the game. Most 4-year-old girls don’t understand this. Watching boxing matches is one of the few things my daddy does with me, so I cherish our time together.

The only sport I saw my father invest himself in was boxing. Sure the requisite bowls that nearly every American household turns to on Thanksgiving, New Year’s Day, and Super Bowl Sunday sometimes played in the background, but boxing held his attention in a different way. It had more meaning. Strong men, many of whom were Black, expressed their anger by beating up their opponents. Perhaps my father, who was also Black, lived vicariously through them. Daddy wasn’t physically violent, but his rage terrified me. I wished he had some other outlet, like exercise, for his frustrations.

I heard about George Foreman’s death on the radio one morning while I was in the kitchen. The grill bearing the champion’s name sat on a pantry shelf not three feet from where I stood. I pull it out every couple of weeks to make hamburgers. My deceased father, who coincidentally was also named George, bought me a George Foreman grill. My father respected his contemporary’s business acumen. Both these Georges had pulled themselves up by their proverbial bootstraps through hard work and entrepreneurialism.

Georges have been very significant in my life. In addition to my father, my grandfather was George. In their home, they were referred to as “Little George” and “Big George,” respectively. Hearing my grandmother and my aunts call my overweight father “little” always struck me as odd. Because their middle names differed, my father wasn’t officially a junior; however, he added the suffix in his 20s to distinguish his finances from his estranged gambling father’s.

My son is also a George. My husband and I chose the name to honor my late father. I use “Baby George” when talking to members of my father's family to differentiate my child, though he is now ten years old, from the other Georges in our line.

Reading the world heavyweight champion’s obituary, I learned that the Foremans followed a similar naming tradition to the Bowers. It made me chuckle. Both families had a Big George, a George Jr., and a Baby George.

My father’s second directorial credit incorporated his love for boxing. In 1982, he directed a Black remake of the film Body and Soul. The flick starred Leon Isaac Kennedy and his wife, the beauty queen Jayne Kennedy. Muhammad Ali was also billed as one of the stars.

Muhammad Ali was a hero of Daddy’s. Ali embodied confidence; his mental and muscular prowess won him his title as world heavyweight champion and respect for his sport. He also used his platform to speak out against racism and injustice. When we had watched him on television, my father chanted, “Ali, Ali,” alongside fans. The winning athlete’s charisma even got me rooting for him.

My father tried to project that same self-assuredness professionally. Like the majority of the Black men in the ring, he came from a working-class background, yet in the movie business, most of his fellow filmmakers–whether White or Black–had graduated from college. Daddy’s vocational high school degree put him at a comparative disadvantage. Since he couldn’t claim book smarts, he would have to make it through talent, experience, charm, and street smarts.

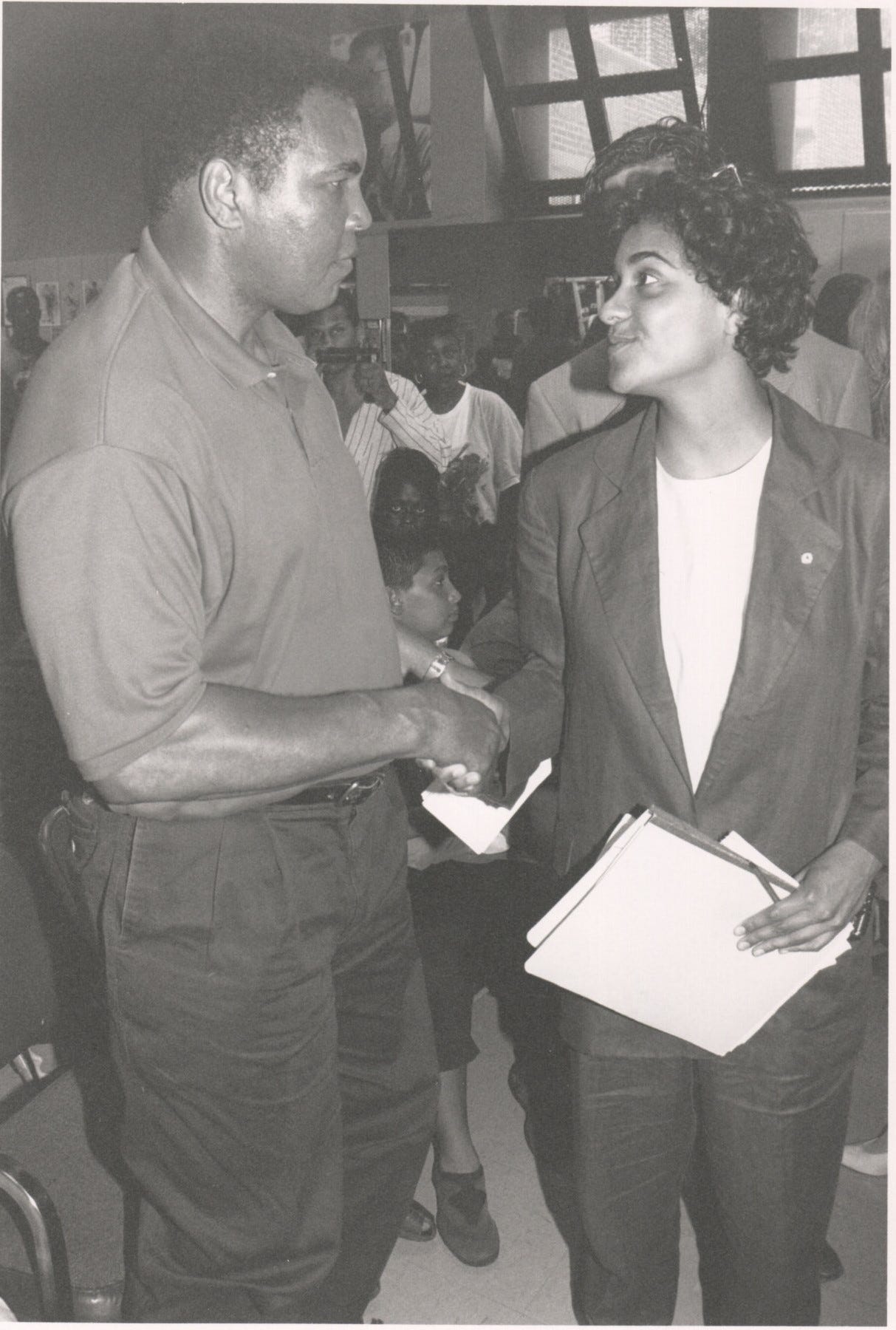

My mother and I visited the Body and Soul set when Ali filmed a cameo. Daddy introduced us to the legend at a boxing gym, and he commented on how pretty I was. The compliment made my father’s day, and I was equally thrilled. Back at school, I showed off the autograph he signed on a sheet of lined paper, which an assistant had pulled from a spiral notebook.

Around boys my familiarity with boxing gave me something to relate to them. In contrast, I didn’t know from baseball, basketball, football, or soccer. A run, basket, touchdown, or goal meant nothing to me, but a knockout was a big deal.

During my adolescence, my father invited his friends to the big-name fights he pre-ordered on cable. While Daddy finished cooking one of his specialties at the stovetop in an apron, I greeted our guests at the front door. These men in their 30s and 40s arrived with six packs of beer in hand. I already knew most of them from our summer backyard cookouts where my father barbequed his famous ribs. (His secret ingredient was the honey he added to Chris’ & Pitt’s Original BBQ sauce.)

After the bell rang to kick off the first boxing round, the men passed around bags of Lays potato chips and cans of Planters salted peanuts or mixed nuts. Multiple bodies packed into our living room, and from the hallway I could only make out the boxing rivals' glistening figures in their colorful satin shorts. I didn’t mind. All the testosterone plus the tasty snacks made the occasion exciting.

Halfway through the boxing match, my father served his delicious spaghetti. He spent hours preparing his mother’s recipe from tin cans of tomatoes and tomato paste, butcher’s sausage, and ground meats. Daddy’s relatively homemade version was much richer than the jarred sauce and hamburger beef my mother topped pasta with, so it didn’t need Parmesan cheese sprinkled on top.

My first job out of college, I attended an event where Muhammad Ali was the guest of honor. It took place at the Thomas Jefferson Recreation Center in East Harlem. For the camera, the champ’s fists knocked the gloves of the boxing club’s young Black and Latino members. The former athlete’s brain trauma had impaired his speech, so his schtick was already toned down. After telling the icon my name, I recounted our Body and Soul connection. His smiles and grunts confirmed his recollection of our previous meeting. I called my father that evening to recount the exchange. We commiserated that even the “Greatest” was not immune to boxing-related injury

Concurrently, the George Foreman Grill hit the market. Daddy extolled both its efficiency and its fat-reduction virtues. (In his on-again, off-again relationship with dieting, this coincided with a healthy eating phase.) Since I lived alone, my father bought me one. Being a Black-owned operation, or rather a Black-endorsed product, my dad was happy to support another brother. I hadn’t asked for the electric grill, but it wasn’t unusual for my father to purchase items like this from infomercials or QVC. He, too, was entrepreneurial with a small side business in addition to his film work.

True to both Georges’ words, the clam-shell Lean Mean Fat-Reducing Grilling Machine cooked meat as well as, if not better than, pan frying. Grilling wasn’t as fattening as cooking a turkey burger or a boneless chicken breast in its fat. Grease collected from the sloped surface into an indented lip at the bottom and then drained into a detached oval tray. As I went to clean the contraption, I couldn’t resist picking at the crispy tidbits that stuck in the grooves and dipping my finger in the seasoned juices that dripped into that crevice at its edge. I probably consumed the same amount of calories I saved from grilling. Even without my post-meal nibbling, washing the grill was easier than scrubbing a pan.

My father’s original gift got lost amid several moves in the last 30 years, so I purchased the one currently stored beside other kitchen appliances. It’s gotten so much use that the white plastic cover has chipped. Even though I refer to the grill as “the George Foreman,” the boxing businessman doesn’t come to mind when I use it. I think about how I bonded with my self-absorbed father by adopting his love of boxing.

Quite frankly, I lost interest in the sport once Robin Givens’ former husband bit off his opponent’s ear. It became a side show.

Nonetheles, Georges have brought a great deal to my life. Boxing. Cooking. Thank you, George Foreman.

Loved learning about all your Georges !

Another beautiful essay, Tanya.